The first ten amendments to the United States Constitution were added because of widespread concern that the country’s plan of government as ratified in 1787, lacked safeguards to protect against abuse of government power.

The first of these amendments, adopted in 1789, added five basic “freedoms” deemed essential to the preservation of individual rights.

One of these was freedom of “the press.”

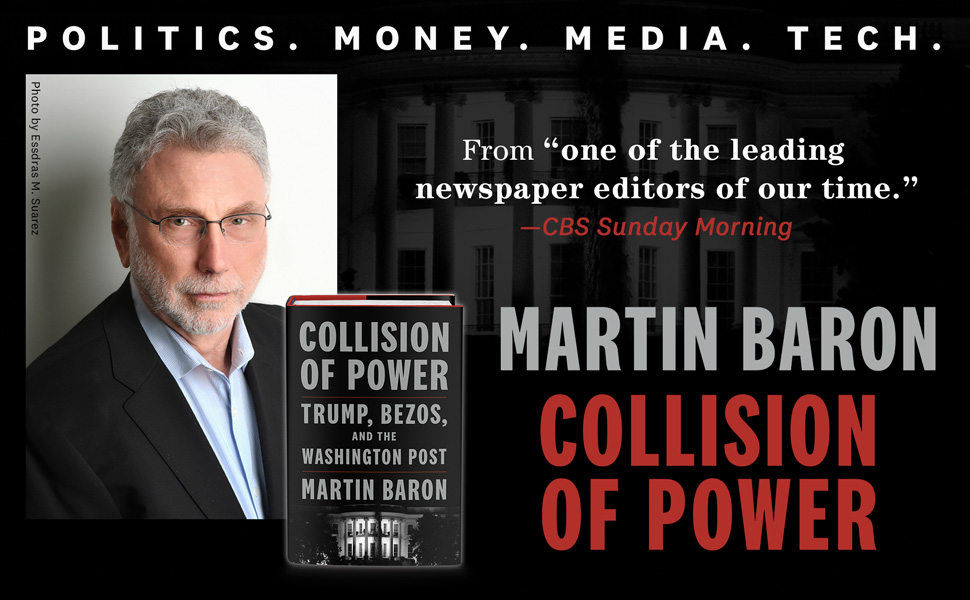

For Martin “Marty” Baron, author of Collision of Power, former editor of the Washington Post and before that The Boston Globe, it is essential that “the press” act as a major bulwark against government-facilitated tyranny.

Without independent newspapers the government could quickly dissolve the rights guaranteed to all Americans by the Bill of Rights.

Baron trusts that a well-informed public, presented with objective, fair, honest, and balanced investigative reporting is essential (and, perhaps, sufficient) to defend democracy against tyranny.

Trusting a well-informed public to make its own decisions is the newspaper’s way of preserving personal rights. If the public has the information it needs, Baron writes, then its decisions (whatever they may be) are democratic.

Providing balanced and fair information to the public is, as Baron explains, no simple task. The Post, for instance, was an independent newspaper that was simultaneously a business enterprise of considerable size, owned by Jeff Bezos of Amazon. As such, it must pay its bills and show a profit to continue to exist.

Perhaps the most immediate challenge under Baron’s tenure was how to increase a readership which had been in serious decline (necessitating the sale of the paper to a wealthy buyer like Bezos).

To do this required hiring investigative reporters and editors who could then write stories that would generate increased reader interest.

It also required a technological revolution in the product itself: from printed physical newspapers sold per copy, to online digital newspapers sold with subscriptions and protected by a paywall.

In addition, technological innovations during Baron’s editorship raised new problems for reporters wanting to write honest and objective accounts.

Intention and time (and therefore money) were needed to track down unsubstantiated online leaks; whistle blower reports, stolen secret documents, possibly false or misleading reports from other media sources, and “news” created by foreign governments.

The Post’s coverage of Russia’s interventions to support Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential election illustrate the technological and legal difficulties the Post faced as a newspaper wishing to offer its readers a fair and objective “truth”.

Donald Trump himself became a third category of challenges (in addition to technological changes and business demands) that Baron and the Washington Post staff faced in their efforts to keep the newspaper reading public well informed. Baron writes that President Trump’s use of presidential power turned the government into “a weapon of intimidation against the free press.”

Collision of Power includes numerous examples of this, many of them now quite familiar. What was unfamiliar and entirely new, according to Baron, was the “weaponization” of the government under Trump to undermine the value of a “free press.”

There was, as well, another, fourth obstacle Baron and the Post struggled with in its defense of First Amendment rights. Baron believed firmly that for the public to be well informed, a newspaper must offer its readers “objective,” “fair,” and “honest” reporting. Significant portions of the book are devoted to this issue.

It is, I believe, a topic well worth further attention.

What did it mean for the Washington Post to be “fair” in its reporting?

During his tenure as editor Baron strongly opposed (often younger) reporters’ willingness to allow their own experiences and views into their reporting.

Baron’s traditional approach required equal attention to the major voices in any controversy – most often defined as the two dominant sides.

One result of this traditional “fair” reporting was that President Trump’s views, even when determined by Post fact checkers to be false or misleading, were given equal attention to those of his opponents. This put the Post in the position of reporting misleading and false statements as the day’s news. If readers were to make their decisions based on the available “news” as reported in the Post (and, of course, other newspapers which followed the same “fair” tradition), then the Post was undermining its own role as a creator of an informed public.

What would it mean for the Washington Post to be “objective” in its reporting?

To be objective assumes that there is one way of viewing reality all honest and fair folks would agree is “accurate.” My reading of Collision of Power suggests that, while it’s an implicit belief for Marty Baron, his own experience indicates objectivity, as he understands it, is not possible.

For example, he decries his reporters demand for across the board pay increases – especially, they say, given the enormous wealth of the Post’s owner, Jeff Bezos, of Amazon. This is wrong, Baron writes. Just because the owner is rich doesn’t make the business a charity case. Even more importantly for Baron, pay raises should be based on merit, never equally for all. Baron is clear that he is right, and the staff incorrect. Even more to the point, Editor Baron, and the Post’s staff, both “know” that they are assessing the situation “fairly” and “honestly.”

Similarly, on another occasion, when the Post’s management is confronted by black reporters and others of color over questions of race and equity at the newspaper, Baron’s “defense” of the paper’s efforts is publicly derided and scoffed at by reporters and other staff. Again, there is no cross over between Baron’s “fair and honest” assessment, and that of others at the Washington Post.

These two examples show why “honesty” and “fairness” are not always sufficient to enable “objective” reporting. Baron is “just,” “fair,” and “honest” in his appraisal of what is happening. But then, so are those others who conclude that the Post is not treating staff fairly and equally.

Integrity and honesty are crucial for the Post to fulfill its role as a First Amendment defender of democracy. Belief in one own’s objectivity, however, can lead to a self-righteous conclusion that your own vision is clear and fair—but others are not (unless they agree with the speaker).

Read Collision of Power if you find yourself fascinated by an insider’s account of the struggles, and achievements, of a leading U.S. newspaper during a time of great technological, business, and political upheavals.