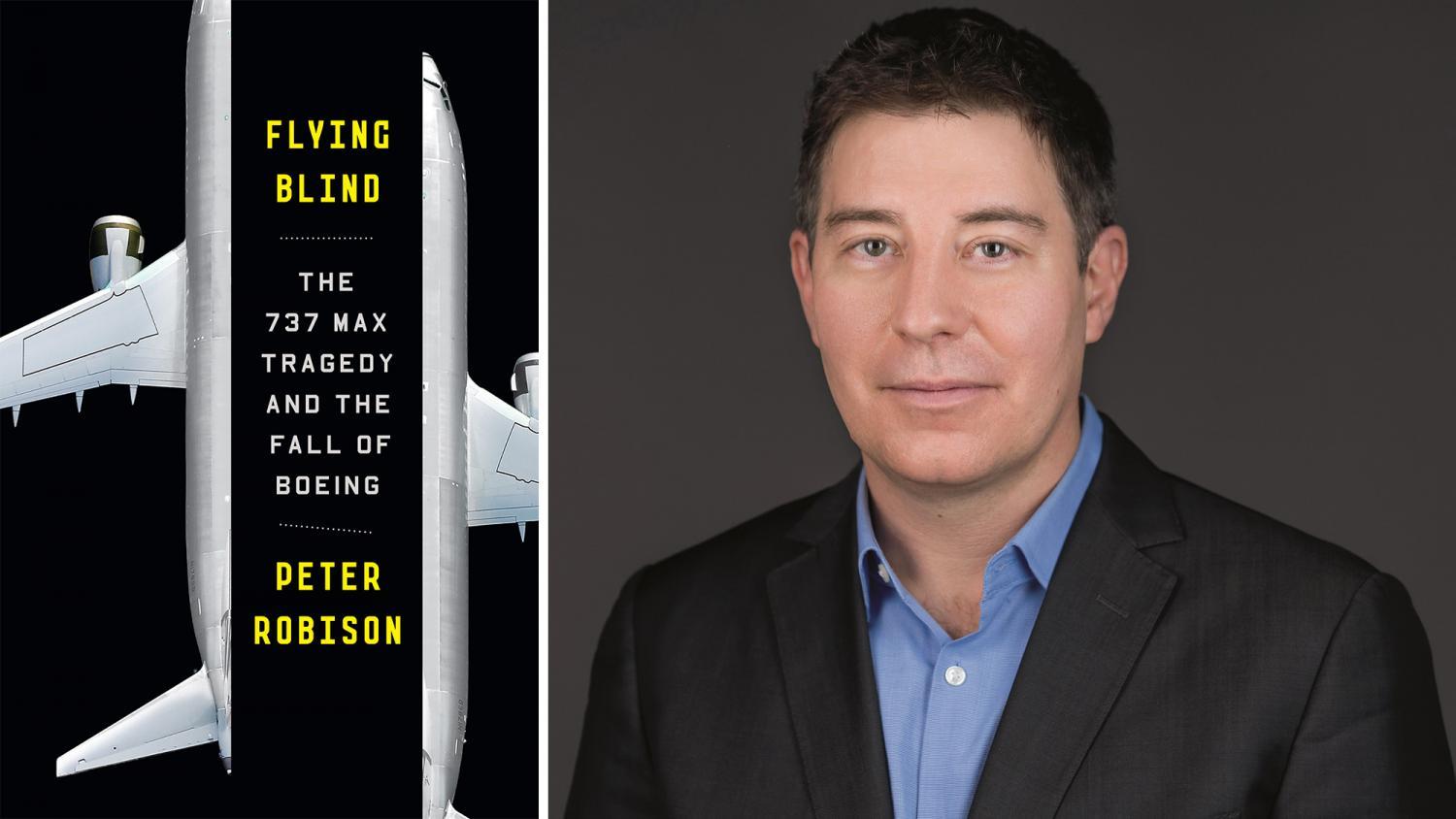

Although multinational corporations are often accused of putting profit over people, Peter Robison’s Flying Blind: The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing makes the case that there once was a time when America’s biggest aerospace company was a more responsible and people-centric firm, focused on its the success of its business as opposed to just balance sheets and stock prices.

By exploring and retelling Boeing’s history, Robison offers a profile of a company devoted to laudable achievements in aerospace engineering — a company willing to sacrifice millions to ensure its aircraft were the safest available.

Leaders and engineers are introduced as proud of the company they work for, one that is renowned for innovation as well as transparency.

Boeing’s reputation for transparency was well maintained, leading the company to take full responsibility for the 1985 747 crash that killed five hundred and twenty people in Japan. Robison contrasts that sterling reputation with Boeing’s woeful public image today. By examining Boeing’s highest achievements as well as its most distressing failures, Robison empowers readers to better understand the sequence of ill-fated decisions that have brought Boeing where it is today.

The first section of the book establishes Boeing’s rise to prominence, starting with the development of planes like the B‑29 Superfortress, a long-range bomber aircraft flown in the latter phases of World War II. (The Superfortress was built in Puget Sound, and gets its name from its smaller predecessor, the B‑17 Flying Fortress, which was already in use at the time the war broke out.)

A major victory for Boeing coming out of the war was the extensive data collected from an Aeronautical Research Institute in Germany.

Boeing engineers were able to drastically improve designs for their upcoming jet-powered bomber, allowing them to keep up with much larger competitors.

Robison’s first chapters describe Boeing’s early engineering victories in the production of planes for the United States military in language that is easy for those outside of the engineering field to understand.

Boeing’s most prominent early figures, whose personalities are well established, give the book a more personal and entertaining feel.

One of Boeing’s presidents, William Allen, is described as “never travel[ing] without Triscuits and a pair of eyeglasses.” The president’s resolutions for the company from his personal journal are also discussed: Be considerate of my associates’ views, don’t talk too much, let others talk, make sincere efforts to understand labor’s viewpoint, and develop a postwar future for Boeing.

The company’s engineers give life to the story, illustrating a hard working team from humble beginnings, dedicated to and inspired by Boeing’s achievements.

This team called itself The Incredibles.

It included Alvin “Tex” Johnston, who is described as always wearing cowboy boots and once executed a barrel roll over Lake Washington in front of three hundred people, all without telling anyone he was planning to try it.

This team of engineers combined these theatrics with a rigorous devotion to their jobs, coming from all across the country because they believed in Boeing’s vision.

The next few chapters continue through Boeing’s history, including the production of the 737 and 747, reaching a turning point and distinctive tone shift around the early 1990s. Robison explains the cultural shifts through corporate America that were galvanized by Ronald Reagan’s approach to the economy.

This included the idea that profits and shareholders should be the main priority.

For Boeing, the 1990s proved to be an extremely successful era, allowing them to buy one of their oldest existing competitors, but also demonstrated Boeing’s willingness to abandon its founding principles.

The legacy of the resolutions of former president William Allen was replaced by a dedication to maximizing profits at seemingly any cost.

The board saw company-altering turnover, including the addition of General Electric’s Jack Welch, who championed a culture change at Boeing that de-emphasized the importance and value of sound engineering.

As a consequence, Boeing engineers found themselves in a distinctly different environment than what they had expected. People who had studied and aspired for the opportunity to be like The Incredibles were left very disappointed.

One unnamed manager reportedly said: “I hate this new culture… I don’t want to be anybody’s facilitator, I want to come to work and kick some ass.”

The board became increasingly obsessed with pushing Boeing’s stock price higher, a far cry from its past dedication to aerospace innovation.

The 2010s would reveal the consequences of this mentality for Boeing.

With airlines demanding better, more fuel efficient planes, Boeing faced the choice of either upgrading the bestselling, narrow-body 737, which was bringing in a third of their revenue, or designing an entirely new plane.

Additions to the more expensive model included sensors that could make corrections for pilots. These corrections could be overridden in case of an error, but pilots needed to be thoroughly trained on how to do so.

Not only was Boeing able to receive government approval to allow the MAX to go into service without required training, the company even rejected requests from airlines for pilot training. This included Lion Air, whose request for pilot training was denied, precipitating the 737 MAX crash that subsequently killed 189 people.

Robison focuses his concluding chapters on this devastating 737 MAX crash, detailing Boeing’s responses and comparing them to crash responses in the past.

Robison provides a thorough account of Boeing’s current standing and reputation, detailing where it all went wrong and highlighting some of the key villains in Boeing’s story. The final chapters are fast paced and gripping.

Flying Blind was highly engaging and especially thorough. The biographical portraits were well developed and the interviews were very illuminating.

The book’s discussion of economic shifts in corporate America is particularly compelling. Readers from the Seattle area will likely enjoy reading stories about key moments and events that took place in the Pacific Northwest.

Flying Blind is well worth reading and its narrative style makes it easily manageable for anyone who struggles with nonfiction.