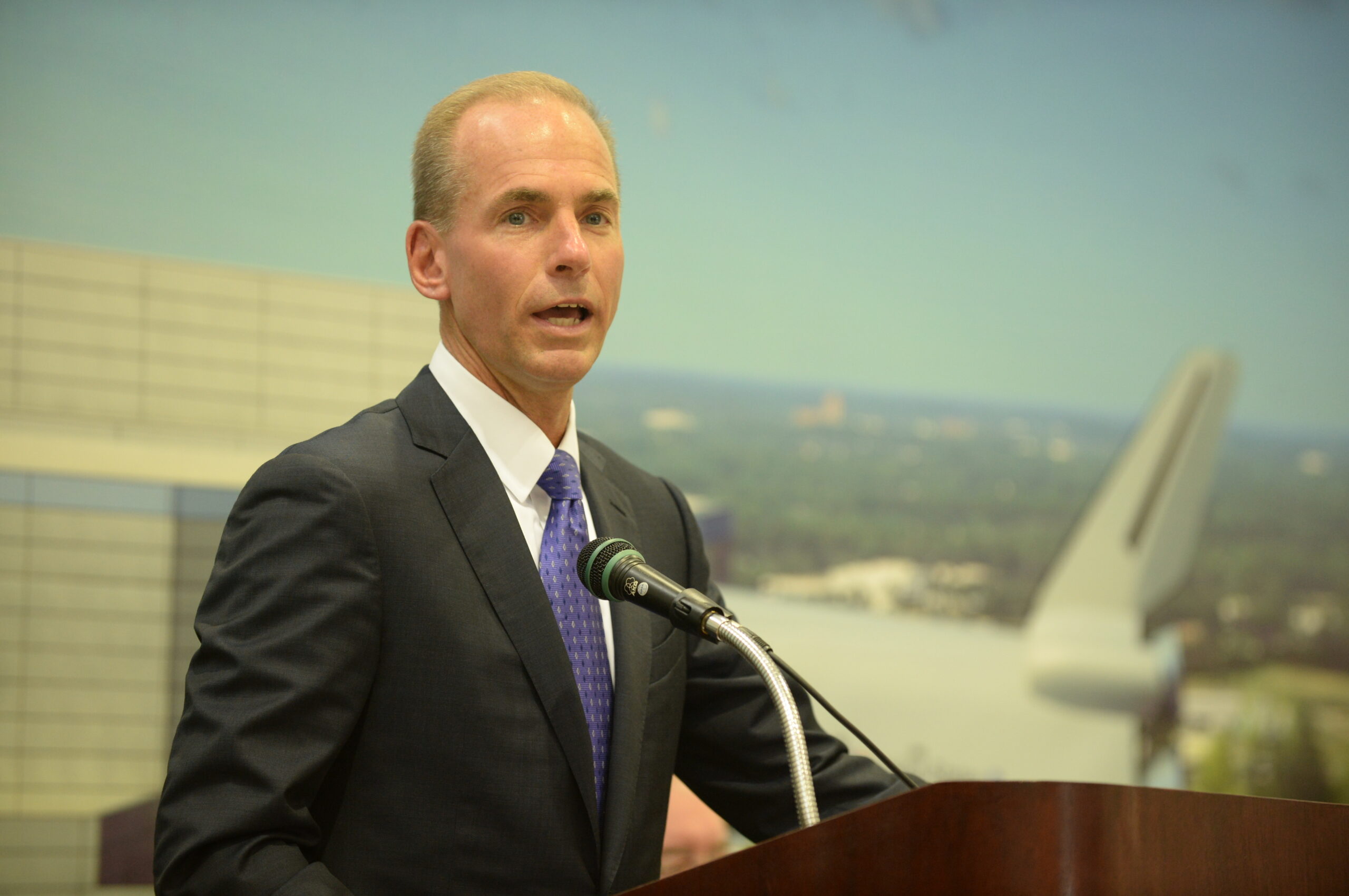

Boeing said on Monday that it had fired its chief executive, Dennis A. Muilenburg, who was unable to stabilize the company after two crashes involving its best-selling 737 Max plane killed 346 people and set off the worst crisis in the manufacturing giant’s 103-year history.

The plane has been grounded by regulators since March, and the company and its airline customers have lost billions of dollars. Boeing has faced a series of delays as it tries to fix the Max, and the jetliner’s return to the air remains months away at best.

Boeing [NYSE: BA] announced today that its Board of Directors has named current Chairman, David L. Calhoun, as Chief Executive Officer and President, effective January 13, 2020.

Mr. Calhoun will remain a member of the Board.

In addition, Board member Lawrence W. Kellner will become non-executive Chairman of the Board effective immediately.

Since Calhoun will not become the new chief executive officer right away, one of Muilenburg’s deputies will be in charge for the next few weeks.

Boeing Chief Financial Officer Greg Smith will serve as interim CEO during the brief transition period, while Mr. Calhoun exits his non-Boeing commitments. The Board of Directors decided that a change in leadership was necessary to restore confidence in the Company moving forward as it works to repair relationships with regulators, customers, and all other stakeholders.

Like several of his predecessors, Calhoun is a General Electric import. Bloomberg:

Boeing is turning to a GE veteran to run the company for the third time in less than two decades, as the U.S. planemaker faces scrutiny for its unrelenting focus on shareholder value. The two CEOs who preceded Muilenburg — Jim McNerney and Harry Stonecipher — also rose through the ranks at GE while Jack Welch was chief executive.

Calhoun had been in the running to head Boeing almost 15 years ago, when directors instead selected McNerney. Calhoun ran GE’s aircraft engines division from 2000 through 2004 and ascended to the vice chairman role before leaving the company in 2006.

Affable and diplomatic, he’s also very connected.

Calhoun serves on the Caterpillar Inc. board with Muilenburg and oversees Blackstone’s private equity portfolio.

Muilenburg’s tenure as CEO at Boeing lasted a little over four years. At the time he was installed, the company seemed to be on a solid footing.

But then, about a year ago, tragedy and crisis struck with the crash of Lion Air Flight 610, which was followed by the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 early this year. That eventually prompted the worldwide grounding of the 737 MAX, the “next generation” incarnation of Boeing’s bestselling narrowbody passenger jet.

The MAX remains grounded and its return to service is unknown. The grounding has already cost Boeing billions of dollars and is likely to cost billions more.

Many Boeing critics have argued that top brass the aerospace giant inherited from its all ‑stock 1996 merger with McDonnell Douglas (including Harry Stonecipher) are to blame for the company’s present predicament.

The McDonnell Douglas contingent have often been derisively referred to as bean counters by veteran Boeing workers and retirees, many of whom still justifiably resent the relocation of Boeing’s headquarters from Seattle to Chicago in 2001.

Back in the summer, one commentator took the opportunity to imagine what might have happened if Boeing had never merged with McDonnell Douglas.

This isn’t the first time in Boeing’s post-merger era that it has gotten into trouble as a result of board and C‑Suite mandated corner-cutting by the MD contingent.

When the 787 Dreamliner was on the drawing board, the company’s management figured that the plane could be built much more cheaply by outsourcing a lot of the work that had traditionally been done in-house. Their grand plan backfired spectacularly, causing a series of delays and production problems that cost an enormous amount of money to investigate, diagnose, and rectify.

The 787’s troubles continued even after it entered revenue service.

In 2013, at least four of the first 787s were plagued by electrical system malfunctions stemming from the model’s onboard lithium ion batteries.

The entire 787 fleet was subsequently grounded while the Federal Aviation Administration investigated. The National Transportation Safety Board also launched a probe that resulted in the release of a report in December of 2014.

As bumpy as the 787’s development and early years were, the 737 MAX crisis is worse. The 737 series is Boeing’s crown jewel and its bestseller; unlike the 787 series, it carries a significant percentage of the United States’ domestic air traffic.

Whereas the 787s were allowed to return to the air just a few months after being grounded, the 737 MAX fleet will have been grounded for more than a year by the time it returns to service. Muilenburg had reportedly been leaning on the Federal Aviation Administration to give his optimistic projections about the 737 MAX’s return to service credence, but had been rebuffed by the agency.

Safety lapses at the North Charleston plant have drawn the scrutiny of airlines and regulators.

Qatar Airways stopped accepting planes from the factory after manufacturing mishaps damaged jets and delayed deliveries.

Workers have filed nearly a dozen whistle-blower claims and safety complaints with federal regulators, describing issues like defective manufacturing, debris left on planes and pressure to not report violations. Others have sued Boeing, saying they were retaliated against for flagging manufacturing mistakes.

Joseph Clayton, a technician at the North Charleston plant, one of two facilities where the Dreamliner is built, said he routinely found debris dangerously close to wiring beneath cockpits.

“I’ve told my wife that I never plan to fly on it,” he said.

“It’s just a safety issue.”

Muilenburg’s ouster may have given Boeing’s stock a temporary shot in the arm, but what Boeing really needs is a new board of directors and top executives who are committed to the values of safety, integrity, quality, and transparency. The company cannot be successful over the long term if it does not secure leadership committed to transformative change that creates a culture of excellence.

This is a message that many people are offering in response to Muilenburg’s exit.

If Boeing wants to remain a going concern, it must stop antagonizing and undermining its union workforce and pressuring the FAA to let it regulate itself. Obsessively focusing on short term profits is unhealthy and dangerous.

The company could generate a lot of goodwill around these parts if it moved its headquarters from Chicago back to Seattle, where most of its commercial airplanes are still built. Boeing’s executives would undoubtedly benefit from greater geographical proximity to their own key plants and personnel.

Boeing’s board would be wise to begin looking outside of the company for a new leader who can take over from Calhoun and lead the firm into the future. Someone who won’t be afraid to champion wiser governance and management practices. Someone who listens well, thinks critically, and long term. Someone who is a tactful negotiator, calm communicator, and savvy recruiter.

Good leaders can be hard to find, but it’s imperative that Boeing find them if it wants to avoid lurching from the crisis it’s in now to a new one beyond the horizon.