There are some historical questions that are so nuanced, complex, and fundamental to understanding who we are that they must be asked repeatedly.

The new answers are often novel — revisions of earlier ways of thinking about the past. “Revisionist” as an adjective can be used as a pejorative.

New approaches are described as purposeful distortions of the past for political reasons. Yet “new approaches” are constant in all fields of study.

That is how our known world grows and deepens.

Smartphones and the internet are prime examples. In fact, all history writing was revisionist in its time. “Revision” is the foundation stone of learning.

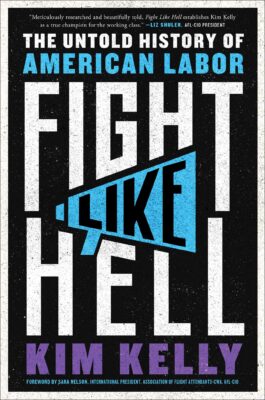

Kim Kelly’s Fight Like Hell: The Untold Story of American Labor wants to be both radical and revisionist. For the book to achieve its intended goals, however, requires some work on the reader’s part.

Chapters in Fight Like Hell are arranged by “industry” – for example, harvesters, miners, metal workers, cleaners. Especially in the first half of the book, these many list-like accounts of people, organizations, and events, chapter by chapter, each briefly described before moving on, can become dulling.

Nor is Fight Like Hell: The Untold Story of American Labor an “untold history.” Much of the text is based on already published work of others, and on widely available documents and primary sources.

Despite these drawbacks, Kelly clearly intends her work to be inspiring. And as Fight Like Hell progresses toward its closing chapters, the urgency of labor history, and the reason for the title itself, become clearer.

Slowly at first, and then with increasing energy, Fight Like Hell brings together radical themes from our nation’s past that make the book a worthwhile read.

It’s these themes, and how Kelly organizes her information to emphasize and support them, that make her account well worth reading.

What are these themes, and what makes them effective?

Here are several examples of the book’s themes (as I read it) that illustrate the potential power of this book:

Who is rewarded for using violence, and who is condemned for using violence?

Which groups use violence to achieve their goals, and then has its use not only condoned but praised and rewarded, tells us what those in power at the time support, and what they condemn.

In other words, we can study labor history for itself and as a lens to understand prevalent political attitudes at different times in our history.

Violence has been used — intentionally and effectively — against organized laborers struggling to gain basic workplace rights that we now largely take for granted. Examples include the Lawrence, Massachusetts, textile strike of 1912, when the governor called out the state militia; the 1877 railroad strike, when private guards, local, state, and federal troops were all mobilized; and the 1894 Pullman Strike, which included a federal injunction against striking workers.

On the other side, the IWW (International Workers of the World), a labor union that used street activism and civil disobedience to recruit members and to bring issues to the attention of the public, were treated as dangerous radicals to be subdued — by state condoned violence, when needed.

Some working people continue to lack the basic work rights that are legally guaranteed to all.

Incarcerated individuals are used extensively to provide services and produce products that are then retailed to the larger public by private businesses.

Paid minuscule wages, often working in dangerous and unhealthy environments, they are without legal recourse to protest their situation.

Kelly places these practices within the larger framework of powerful people using forced labor to support U.S. capitalist enterprise.

Slavery, black codes, and Jim Crow laws are earlier examples.

Many who are not accepted as workers deserving of union support – now and in the past — are in fact workers deserving of labor support and respect.

Women who work at home – in their own home, or in another’s home – often are not accepted as “workers” by organized labor. Launderers, cleaners, and childcare workers, for example, are said to be not “at work” because they conform to a traditional gender role of “women’s responsibilities”. If you can’t “see” a problem, then you can’t recognize it as a problem that needs attention.

The cause of problems for “marginalized” groups is structural. It is not evidence of an individual’s inadequacy.

Business owners as well as labor unions have turned various marginalized groups against each other. Often this has been along racial and ethnic lines, as in the sugar cane fields in Hawaii. It also includes disabled people, gays, lesbians, bisexuals, older workers, and sex workers, among others.

Progress is a class issue.

That positive changes have been the result of grassroots organizing and of militant protests from below, not from above, is fundamental to Fight Like Hell’s understanding of labor history. White, middle class reformers have not been effective. Bayard Rustin’s views serve as an example. Rustin believed that unions generally (and Black unions in particular) were the best way to gain equality and civil rights. The cause of labor is the hope of the world.

In Fight Like Hell, Kim Kelly offers a radical view of the role of labor in the history of the United States. I found that inspiring. And for good reason. It’s fundamental to understanding how the United States has evolved over generations.

While Kelly certainly does not stand alone in either her perspective or her conclusions, it is not the only legitimate view of labor history that is supported by the available evidence. Kelly’s enthusiasm is not in itself sufficient to validate the book’s historical interpretations.

If learning is your goal, it’s important to remember that.