This morning, The Seattle Times ran a very important, above the fold story by statehouse correspondent Joseph O’Sullivan that looks at the chronic underfunding of public health systems in Washington State.

As O’Sullivan reports, the sabotage of our state and county health departments is a tragedy that goes back decades and can be traced back to the adoption of two of Tim Eyman’s earliest initiatives — both of which were ruled unconstitutional, but which were subsequently reinstated by the Legislature anyway.

The problem began, state and local health officials say, with a pair of voter-approved initiatives about twenty years ago.

Initiative 695 removed the state motor vehicle excise tax, a dedicated source of money to public health programs. Shortly after that, voters approved Initiative 747, which limited property tax increases that helped fund local health districts.

It’s important to note that while the doesn’t mention Tim Eyman — which is good in that it allows the narrative to stay focused on what happened to our public health departments — Eyman was the sponsor of both I‑695 and I‑747, and the disinformation he peddled was a major factor in their passage at the ballot box.

Money problems festered as the Great Recession further hammered tax collections, officials say, and as federal funding became more restricted. Those issues created a cycle where every budget brought cuts or difficult spending choices.

“Almost in every budget cycle before I came on board, there had been pretty major cuts,” said Patty Hayes, who in 2014 became the director of Public Health – Seattle & King County.

“And when I came on board six-and-a-half years ago we had a $12 million hole” in the budget.

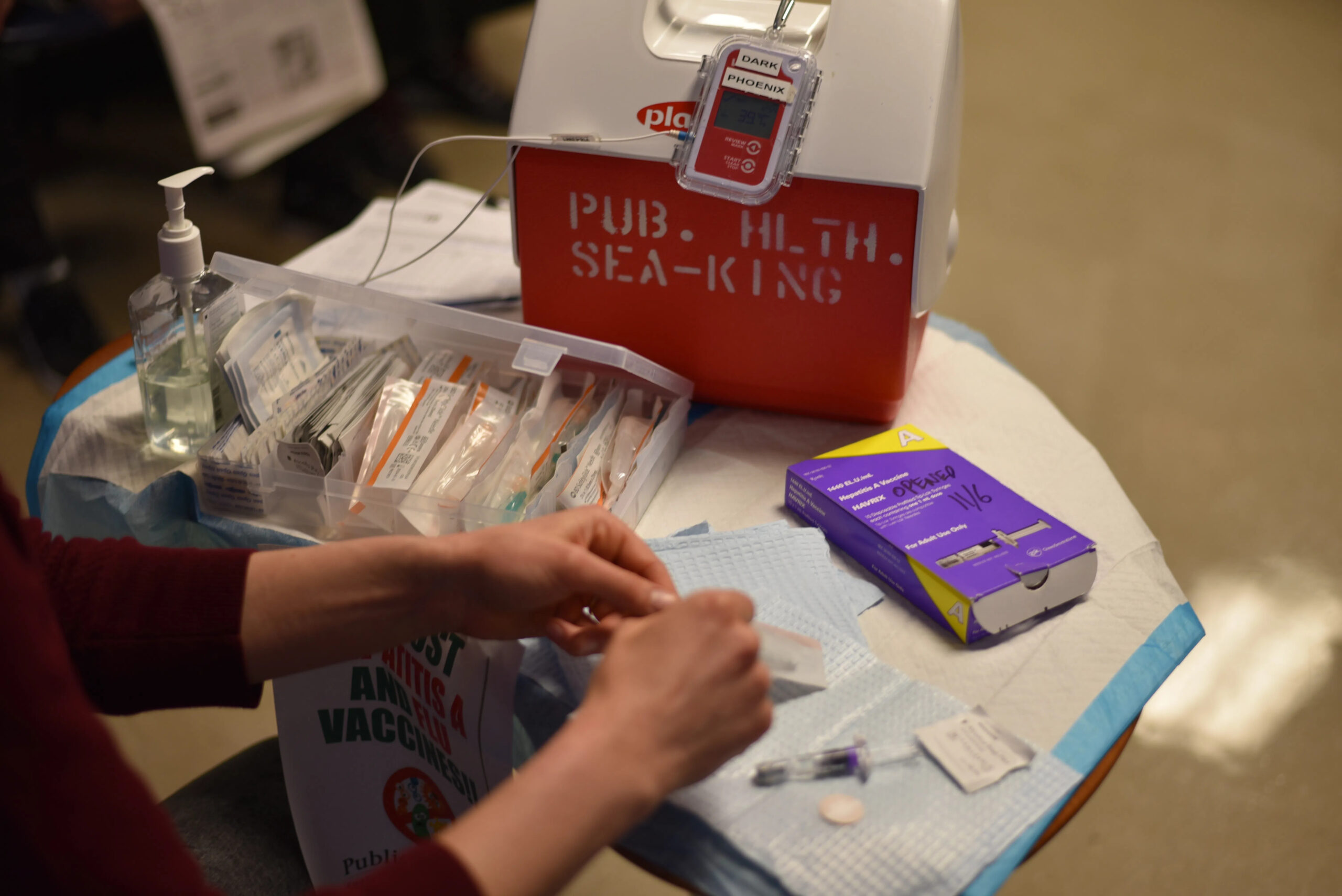

She described a series of hard choices as funding dried up. Vaccine clinics stopped, home visits were trimmed back and planning for emergencies like a pandemic fell by the wayside.

Hayes described the loss of a program for identifying latent tuberculosis as a great example of how public health programs can save significant dollars.

If latent tuberculosis is identified, it can be treated for about $600, said Hayes — compared to $15,000 or more if the person develops the disease and later goes to the hospital.

For over nineteen years, our team at the Northwest Progressive Institute has fought Eyman’s destructive initiatives and worked to remind all Washingtonians that there are two sides to every equation. The truth about taxes is a truth that needs to be constantly told: Taxes power investments in the things that make our communities strong, from hospitals and schools to parks and pools.

Businesses of all sizes rely on public services to operate. The success of the private depends on the public. Consequently, when we defund public services by cutting or limiting taxes, we’re setting ourselves up for pain and misery and failure as a society. We’re still paying the price today for the implementation of Tim Eyman’s earliest destructive initiatives, which have never been repealed or replaced with more progressive revenue sources by state legislators.

In the immediate aftermath of the implementation of I‑695, legislators did a lot of backfilling to offset cuts that would have otherwise been made to public services. Perhaps it might have been better if they hadn’t, because that backfilling exercise created a pretext for Eyman and right wing think tanks like the Washington Policy Center to begin peddling a false narrative about Eyman’s initiatives.

In a pamphlet published in January 2001, WPC’s Paul Guppy and Brett Wilson referred to I‑695 as “a successful tax cutting policy”, writing:

Events have amply demonstrated that the state and local governments have adjusted well to the revenue reduction required by repeal of the MVET. Government agencies have adapted through a combination of increased efficiency, reordered budget priorities, program savings and alternative revenue sources.

Vital government services have not been disrupted. On the whole these programs have continued as before, and in many cases have been improved and expanded, since Initiative 695 passed. Nor has the measure seriously crimped public revenues, since overall spending by the state, counties and cities continues to rise.

It has now been twenty years since the above nonsense was written and I‑695 was implemented. We have the advantage of additional two decades of hindsight with which we can “coolly assess” the impact that gutting the statewide motor vehicle excise tax has had. We can see it’s been very, very destructive.

It was not just public health that took a hit, by the way. So did ferries and local roads and mass transit and a host of other essential public services.

Contrary to what Guppy and Wilson claimed in their “policy brief”, state and local governments did not simply make do with less revenue. Rather, they scaled back and cut back, as O’Sullivan’s story documents. Backfilling may have cushioned the immediate blow, but there was still a blow… a big blow. So big that even decades later, we’re still talking about the damage that I‑695 (and I‑747) inflicted.

We no longer have to argue or wonder about what would or might happen with implementation of I‑695. We now know because we’ve experienced it.

We have the receipts. The I‑695 opposition campaign was prescient in its warnings, while Tim Eyman and the Washington Policy Center were wrong.

It’s tragic that it has taken a pandemic to focus needed attention on the underfunding of public health in Washington State. There is a long list of other essential services like public health that are sadly in a similar boat.

I wrote about one of them yesterday — geologic hazards research.

Seattle, King County, and other populous jurisdictions in the state’s urban core have managed to partially liberate themselves from the jaws of I‑695 and I‑747 by approving a massive number of local levies designed to fund everything from libraries, parks, and hospitals to mass transit and preschool.

Rural communities, on the other hand, have not. They’re still choking even today. O’Sullivan’s story rightly devotes some ink to their plight:

Since 2011, Asotin County Health Administrator Brady Woodbury has watched his staff of more than a dozen dwindle to six. The same staffers making calls for COVID-19 contact tracing must also still handle inspections and responses for septic systems.

“Contact tracing stayed the priority, but once you got enough, you break off and go get an inspection done,” said Woodbury. If a septic system suddenly failed, he added, “we had to stop contact tracing.”

Okanogan County Public Health over the years lost outreach staff who connect with agricultural employees — which include Mexican guest workers — who work with apples, cherries and pears, said Health Officer James Wallace.

“And we suffered because of it, we wanted to test more people, test our farmworkers, provide more communication and education as soon as this pandemic hit,” said Wallace.

“And because we didn’t have the funding and didn’t have the people we were behind the ball on that.”

Emphasis is mine. With any public service, capacity and effectiveness (the ability to provide what the people need) will always be contingent upon funding. Always.

That’s because, contrary to what Tim Eyman wants people to believe, you can’t get something for nothing. The widespread waste, fraud, and abuse the right wing talks about simply doesn’t exist. All they have are unrepresentative anecdotes (some of which are urban legends, not even real stories).

Former State Senator Adam Kline used to show up at Tim Eyman’s press conferences with a copy of the budget and demand to know where the fat was. Eyman would consistently refuse to answer, because he didn’t have an answer.

Public agencies can’t pay their employees with imaginary money, or afford supplies and materials that projects require merely by becoming more efficient.

Slashing taxes means slashing investments.That’s the other side of the equation the right wing doesn’t like talking about: the return. What comes back to us.

Taxes transform dollars into public goods that none of us could afford on our own. And unlike many business ventures in the private sector, taxes are a very safe form of investment. In fact, they’re pretty much the safest form of investment there is. We know what investing in public health can do for us, for instance.

When public health had a dedicated funding source (the MVET) it didn’t have to compete against other public services for scarce dollars in years in which tax collections were not as strong and there were fewer dollars to be appropriated.

Perhaps, in addition to a rainy day fund, Washington State needs a special services fund specifically for low profile but super important public services like health departments or geologic hazards research or wildfire prevention.

We simply cannot go on as we have been for the last two decades.

At least one thing has changed in the intervening years: Democratic state legislators appear to have learned that reinstating Tim Eyman initiatives is bad. So while I‑976 (Eyman’s most attempt to defund public services he doesn’t like, which was overturned by the Supreme Court last year) will stay dead, the mistakes of the early 2000s still need correcting. The revenue that Eyman’s early initiatives have choked off needs to be restored to secure Washington’s future.