U.S. House Republicans are grappling with internal strife as Representatives Mike Gallagher and Ken Buck resign, while Speaker Mike Johnson will have to contend with an effort to oust him from Marjorie Taylor Greene when the chamber reconvenes in April.

New 2024 legislative maps offer historic opportunities for Latino representation and Democratic pickups across Washington

Read Andrew Hong’s analysis of the new 2024 maps adopted by federal court order following a victorious Voting Rights Act lawsuit, which could potentially alter the state’s legislative balance of power.

Contest for WA-06 heats up as Emily Randall, Hilary Franz unveil prominent new endorsers

State Senator Emily Randall and the state’s Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz, both Democrats, are lining up support for a seat that does not often come open.

Tim Eyman wants to contest initiative filing fee increase, but has no grounds for doing so

The former prolific promoter of initiatives wants to bring a lawsuit to overturn the filing fee increase, but the law expressly gives the Secretary of State the authority to increase the fee.

Jessica Bateman, Lisa Parshley ready to provide orderly succession in 22nd LD

In the wake of Senator Sam Hunt’s retirement, State Representative Jessica Bateman has decided to run for the upper chamber with his endorsement, while Olympia City Councilmember Lisa Parshley will seek Bateman’s seat.

Despite having withdrawn, Nikki Haley still garnered over 20% of the early vote in Washington’s Republican presidential primary

A sizeable chunk of the the electorate found ways to register dissatisfaction with their 2024 choices, particularly on the GOP side, with Trump’s nearly-decade long takeover of the Republican Party.

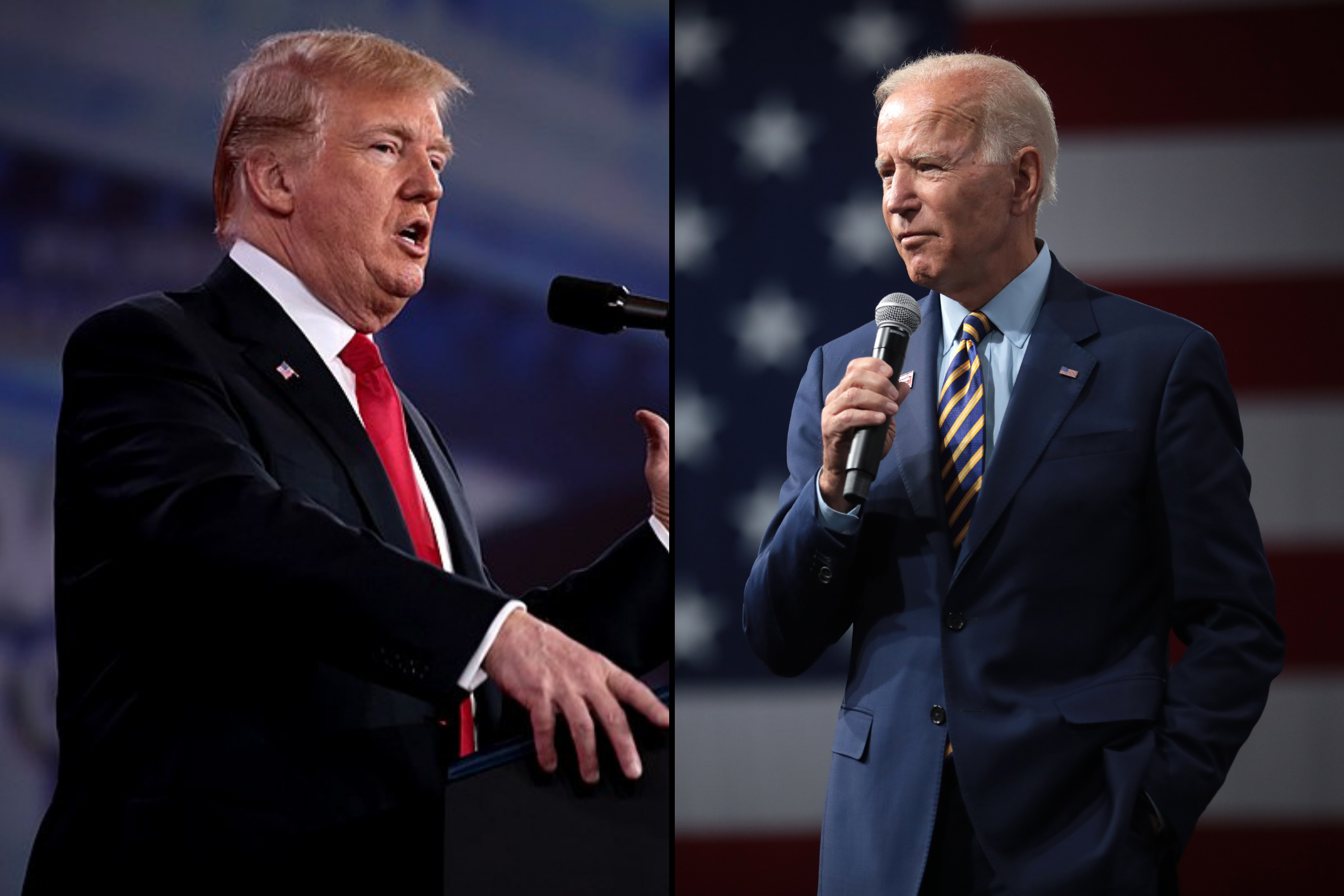

As expected, Joe Biden and Donald Trump cruise in Washington presidential primary

With 1,254,074 total ballots counted so far, the two presumptive nominees — our incumbent president and his neofascist predecessor — have each cruised to victory, vanquishing their withdrawn opponents without any difficulty.

Joe Biden clinches the 2024 Democratic nomination for President of the United States

Biden’s renomination is now effectively assured, though it has not been in doubt given that he had no credible opposition from other Democrats.

Cult above country: Mitch McConnell again bends the knee to Donald Trump

Despite the January 6th insurrection, despite Trump’s invitation to Russia to do whatever it wants to America’s allies, despite the court judgments affirming that he is a fraudster and liar, Mitch McConnell is endorsing Donald Trump. Again.

Book Review: Democracy Awakening explores how elites have subverted American ideals

Read NPI’s review of Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America, by Heather Cox Richardson.

Initiative reform takes a leap forward in Washington thanks to Secretary Steve Hobbs

The long overdue reforms, which our team at NPI urged the office to adopt through its rulemaking process, consist of an increase in the filing fee from five dollars to $156, the indexing of the filing fee to inflation going forward, and the use of a partly randomized string of numbers to classify initiatives.

The best lines from President Biden’s incredible 2024 State of the Union address

The President spoke with deep conviction and from the heart. He fiercely and passionately defended the values that most Americans hold dear. He laid out his accomplishments, vision, and proposed policy directions very effectively.

President Biden throws down the gauntlet in impassioned 2024 State of the Union speech

In his annual address to Congress, the President sought to draw a strong contrast with his predecessor and 2024 general election opponent while making the case for reproductive freedom, climate action, gun responsibility, economic justice, and support for Ukraine. He also announced new relief measures for Palestinians suffering in Gaza.

DONE! Governor Inslee signs legislation ending child marriage in Washington

As of June 6th, Washington will require that both parties entering into a civil marriage be at least eighteen years of age.