“We are the role models for other girls, showing them that they can live free,” says Frozan, a member of the Women’s National Cycling Team of Afghanistan.

She is one of a small group of brave young women in Kabul who risk their lives by riding bicycles in a country where the large influence of the Taliban creates dangers for all, but especially for women. Their lives are very restricted by extremists bent on enforcing their ideals, with violence if necessary.

Frozan and other women cyclists are the inspiring subjects of “Afghan Cycles”, directed by Seattle local Sarah Menzies. The film had its U.S. premiere at The Seattle International Film Festival on May 20th.

I asked Menzies how she first learned about these trail-blazing women.

“A friend and colleague of mine, Shannon Galpin, originally told me about the National Team in Kabul,” Menzies said. “She had been doing different types of aid work in Afghanistan and was interested in shifting her focus toward supporting the groundswell of cyclists that was just beginning to gain momentum. That was back in 2013. That spring we went to Kabul to meet the women that made up the team and see if there was a story there.”

Menzies was originally planning on making a short film, but she realized almost immediately that there was a much bigger story to be told. “Thus began our 5 year production of Afghan Cycles,” she said.

Frozan and the other members of the time face many challenges to pursuing cycling. The Taliban still controls much of Afghanistan, and even in those areas where there is not a strong Taliban presence, the influence of their extremism is still felt.

Frozan and the other members of the time face many challenges to pursuing cycling. The Taliban still controls much of Afghanistan, and even in those areas where there is not a strong Taliban presence, the influence of their extremism is still felt.

Women’s bodies must be fully covered, so the team members train in long sleeves, pants, and with their headscarves under their helmets.

But even so, some people still find what they are wearing to be inappropriate and what they are doing indecent.

“Afghanistan is one of the most difficult countries in the world for women, there’s no question about that,” says Heather Barr, a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch featured in the film. She says there are large rural areas, controlled by the Taliban, where women don’t even leave their home.

Even in less-conservative Kabul and Northern parts of the country, women must have the permission of their father or husband to go anywhere.

Bamiyan also has a women’s cycling team, but one member had to quit because her brother did not approve of her being on the team. But despite the challenges, these brave women are determined to continue in their sport, not just for themselves but to break down barriers for women in their country.

Says Frozan: “We want to bring a biking culture to all girls, so they are able to use the bicycle to go to school, university, the city, the market, to get groceries by themselves.”

Frozan’s mother remembers when there was peace in Afghanistan. It was a democracy and women had freedom to wear and do what they wanted.

She hopes things will change and be stable again.

“My hope is not only for my daughter, but for all the people of Afghanistan, especially for the girls and the women, to be able to stand on their own feet.”

When I asked Menzies if she thought things in Afghanistan are getting better or worse right now, she was not optimistic.

“Unfortunately things are getting worse,” she said.

“It’s been very difficult to be so far away promoting this film knowing that many of our characters are still there living in constant fear.”

I also Menzies if she worried about her safety while she was in Afghanistan making the film.

“Being in Afghanistan certainly has an inherent risk that I don’t want to downplay. However much of my time there was spent in more progressive areas where women are able to get on bicycles for the most part. In other parts of the country where the Taliban is the governing force, a woman on a bicycle would be a death sentence. While my experience was relatively sheltered, I certainly kept my eyes open and remained focused on my surroundings. Things happen, you can easily be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Afghans know that reality all too well.”

Yet the women of the cycle team face the risks every day and to blaze a trail for all the women of Afghanistan.

Follow the film on Facebook to find out about their upcoming screenings.

Another very difficult country for women is Saudi Arabia. It is the home country of Hissa Hilal, who in 2010 became known throughout the Middle East, and indeed the world, not just for being a woman breaking ground in an arena dominated by men, but for directly calling out religious extremism while doing it.

Another very difficult country for women is Saudi Arabia. It is the home country of Hissa Hilal, who in 2010 became known throughout the Middle East, and indeed the world, not just for being a woman breaking ground in an arena dominated by men, but for directly calling out religious extremism while doing it.

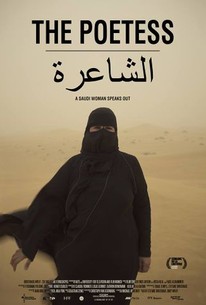

Her story is the subject of another film featured at SIFF this year, “The Poetess.”

On screen for almost the entire film, we never see more than her eyes and the skin just around them, as she wears a niqab, a type of covering not just for her head but her face as well. Women in Saudi Arabia must remain covered at all times when outside the home, or face arrest from the extremist religious forces empowered by the King to control education, culture, and the media.

To even leave the home, women must have permission from their husbands.

In “Million’s Poet,” a show made in the United Arab Emirates and immensely popular throughout the Arab world, Hilal was the first woman to advance to the finals. Called the “American Idol” of poetry, contestants on the show read the poems they have composed in the traditional Nabati style.

Judges on the show praised Hilal for her impressive skill in this respected Arab art form. While a few other women had been on the show before, Hilal was clearly the most talented and advanced further than any women had in previous seasons of the show. But what made her achievement even more amazing was the topics she addressed in her poems.

She spoke of the relationship between men and women, and their roles in Saudi society. In the third round of the competition, her poem, titled “Fatwas”, attacked the repressive edicts issued by religious leaders. It was after a journalist wrote an article about Hilal and this poem that, in Hilal’s words, “everything exploded.”

Media from all over the world were interviewing her and doing stories on her and the show. While Hilal, who describes herself as a moderate Muslim woman, used the interviews as a vehicle to continue to speak out against religious extremism, she also started receiving many threats.

“If they kill me, I am a martyr for humanity,” said Hilal.

Countering the threats, Hilal was also contacted by Arabs and Muslims around that world who thanked her for speaking out and to voice their support for her.

Hilal said that the fatwas and rules imposed by religious extremists are not true Islam, but “political religion.” She notes the history of women’s attire such as burqas, which made sense when Bedoin women wore them to protect themselves from the dust and sun of the desert, but which extremists started forcing women to wear as they gained power in the early 1980s.

There aren’t just strict rules on women’s dress, but on social interacted between the sexes. Women and men cannot gather in the same place in Saudi Arabia, and the rules are so rigid that a woman cannot even walk into a room and greet her male relatives.

“When you isolate women, you isolate the soul of the whole society,” said Hilal.

While Hilal did not win “Million’s Poet”, she placed higher than any woman ever had, and drew great support and attention to the fight against religious extremism in Saudi Arabia and throughout the Middle East.

It is noted at the end of the film that in 2016, the King stripped the religious authorities of power, so they can no longer arrest individuals for things like violating the dress code.

However, women still must get permission from their husbands to do things like work or travel. If more women like Hilal (and men, too!) start to stand up, speak out, and push back against religious extremism, more significant progress can be made towards full freedom for women and all members of Arab society.

Hilal and the women cyclists of Afghanistan are truly passionate, brave, and dedicated women who were inspiring subjects for these excellent documentaries.